A few anecdotes of Mr. Feynman and mine

I visited the ArtScience Museum at Marina Bay Sands this Friday, and met Mr. Richard P. Feynman in quotes, diagrams, and pictures. Before that, I had only met him in words, in his two quasi-auto-biographies Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman and The pleasure of finding things out. So although he had died before I was born, I still feel I know him somehow. I am fascinated and shaped by many who I have never met in person. Mr. Feynman is probably one of them.

He was born into a non-practicing Jewish family, and had a creative and careless childhood. He had a compulsive need to solve puzzles since young, which his father cherished and curated. In fact, many fundamental physical laws were gently instilled into casual conversations like this:

Little Richard: Pop, I noticed something: When I pull the wagon the ball rolls to the back of the wagon, and when I’m pulling it along and I suddenly stop, the ball rolls to the front of the wagon. why is that?

Richard’s Dad: That nobody knows… The general principle is that things that are moving try to keep on moving and things that are standing still tend to stand still unless you push on them hard. This tendency is called inertia but nobody knows why it’s true.

Feynman’s father barely finished high school, but he knew how to explain something plainly and clearly, though he often didn’t know the name of that something. So Feynman learnt early the vanity of name-dropping, and poked many flaws and trivialities of his colleagues in conferences and seminars. Some of those exposed were to be Nobel laureates.

I also had a somewhat similar childhood. My father majored in physics in college, and worked as a maths teacher after graduation, till the living burden compelled him to become a businessman. I inherited part of his talent in maths and physics, and was enraptured by the classical maths and physics puzzles for years. My parents didn’t care about my schoolwork, so neither did I. I spent all my free time tackling those puzzles and pestering my parents with questions. Eventually, the amount of questions became unbearable, so my parents bought me a set of encyclopaedia. I read them all. I’m supposed to be a scientist then, why would I become a PhD student in communication studies? This is another story, I’ll probably share it in another post.

How my curiosity in natural science waned I do not remember, but I do remember the taste of passion. To be immersed in something that you love, when everything else just retreats into the background, is a bliss. It’s unforgettable. I may not be able to relive that experience myself, but I immediately recognise this passion if I see it in someone else, and yeah, unmistakably.

I saw such passion, fused with fun and humour, in Feynman. That’s a rare combination. I had many science role models as a kid. Our government propaganda was full of stories of Mr. Qian XueSen (the physicist that created the Chinese version of atomic bomb) and Mr. Chen JingRun (the mathematician that fired the closest shot at the Goldbach’s conjecture). I understood that they were brilliant, hard-working, and loyal. But I wondered, did they ever joke, did they ever enjoy life? I could never resonate anything with them, they were insurmountable mountains. But I saw Feynman as someone who I can joke with shall I ever ran into him at a conference or in a seminar. (Self-disclaimer: I have no problem joking with professors 50+ years my senior, already did that with several at Oxford.)

Feynman was passionate about teaching, drinking, wonderfully smart women, money (yeah no exception), but most of all, physics. Well, his first love was maths, but he thought it too abstract so chose to major in electrical engineering instead. Then he realised he had gone too far, so changed camp to physics, and it became his love of life ever since. We could perhaps take a glimpse of his mixed passion from the following anecdote. While he was at CalTech, he tried to resist the temptation of accepting an alluring offer from Chicago U by not enquiring the salary package, then by lamenting it when the amount was revealed to him:

After reading the salary, I’ve decided that I must refuse. The reason I have to refuse a salary like that is I would be able to do what I’ve always wanted to do—get a wonderful mistress, put her up in an apartment, buy her nice things … With the salary you have offered, I could actually do that, and I know what would happen to me. I’d worry about her, what she’s doing; I’d get into arguments when I come home, and so on. All this bother would make me uncomfortable and unhappy. I wouldn’t be able to do physics well, and it would be a big mess! What I’ve always wanted to do would be bad for me, so I’ve decided that I can’t accept your offer.

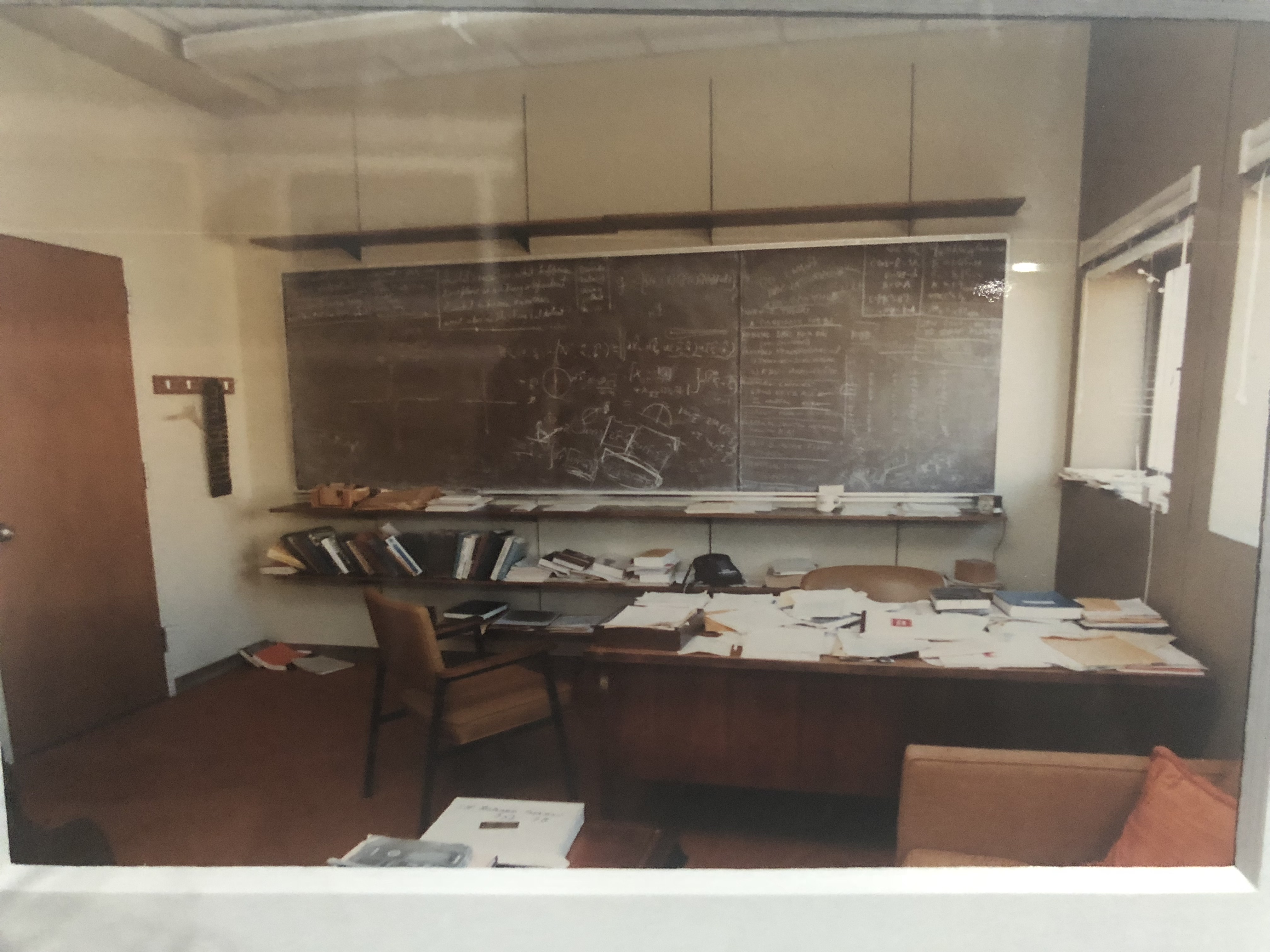

How genuine and candid, I admire that! And when I saw Feynman’s office, I almost burst into tears. Shall I use it as a self-defence when others complain how messy my desks are?

Or shall I use this one (Feynman dressed in Brazilian costume, dancing) instead when others accuse me of being crazy?

My all-time favourite is his soliloquy of what to do after being burned-out. I was on the verge of burn-out many times during my PhD. The sad truth is that though I recovered, I never experienced the joy and light-heartedness that Feynman expressed. Perhaps I need to be infected by his passion.

Then I had another thought: Physics disgusts me a little bit now, but I used to enjoy doing physics. Why did I enjoy it? I used to play with it. I used to do whatever I felt like doing—it didn’t have to do with whether it was important for the development of nuclear physics, but whether it was interesting and amusing for me to play with. When I was in high school, I’d see water running out of a faucet growing narrower, and wonder if I could figure out what determines that curve. I found it was rather easy to do. I didn’t have to do it; it wasn’t important for the future of science; somebody else had already done it. That didn’t make any difference: I’d invent things and play with things for my own entertainment.

So I got this new attitude. Now that I am burned out and I’ll never accomplish anything, I’ve got this nice position at the university teaching classes which I rather enjoy, and just like I read the Arabian Nights for pleasure, I’m going to play with physics, whenever I want to, without worrying about any importance whatsoever.” … Within a week I was in the cafeteria and some guy, fooling around, throws a plate in the air. As the plate went up in the air I saw it wobble, and I noticed the red medallion of Cornell on the plate going around. It was pretty obvious to me that the medallion went around faster than the wobbling. … The diagrams and the whole business that I got the Nobel Prize for came from that piddling around with the wobbling plate.”

Excerpt From: Richard P. Feynman. Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, Part 4: Dignified Professor

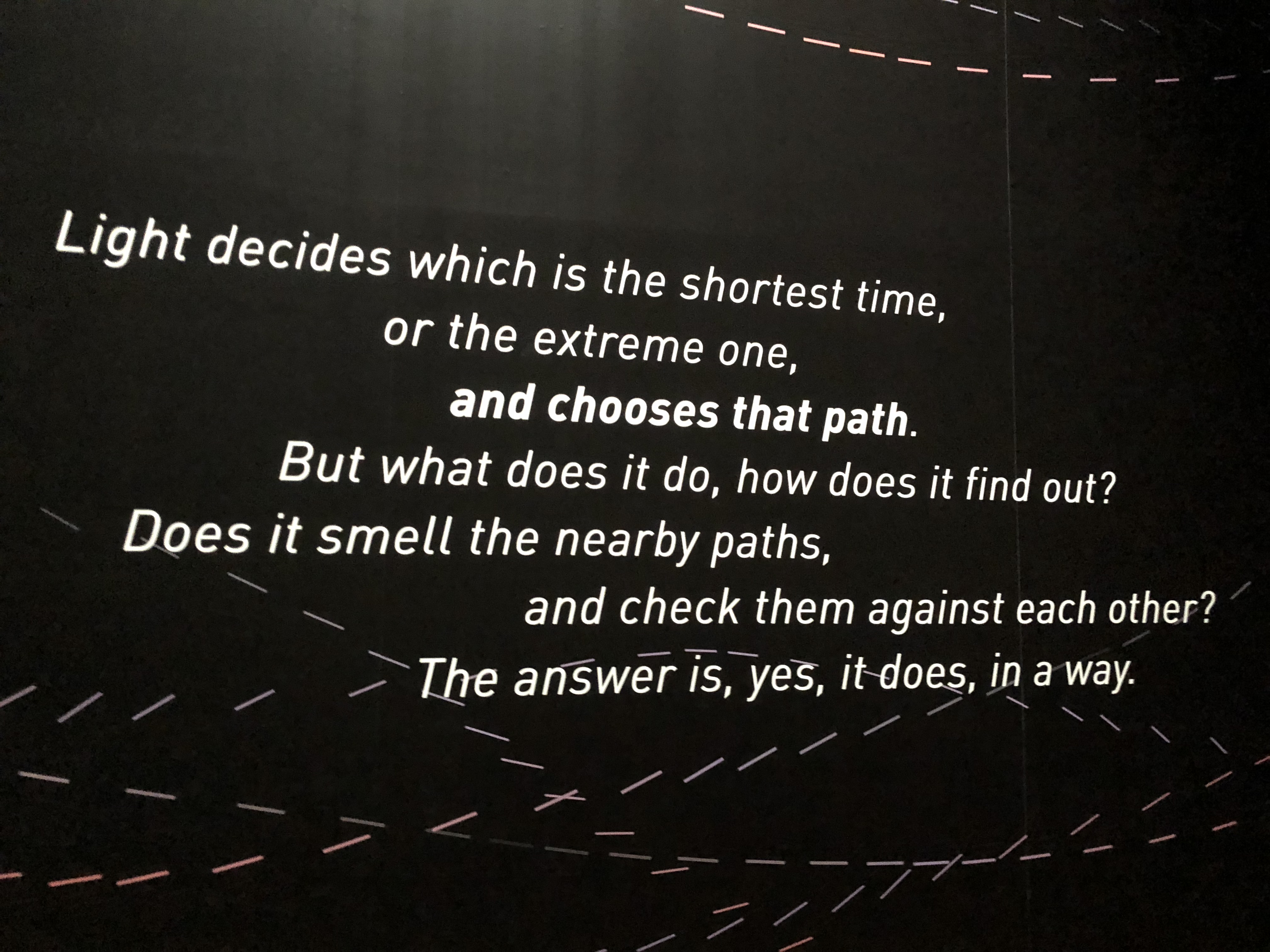

Perhaps I’m already infected. His light must have reached me, if his all possible path theory of light holds true.